Coaching vs Tutoring

Most people are familiar with tutors: these are often teachers or older students looking to supplement their incomes by going over material which their tutees have already covered in school. They might also help children prepare for entrance examinations to various institutions.

Academic coaching is different: coaching does not aim to re-teach material which students have already covered in school. Nor does it aim to help students with specific pieces of homework. Coaching instead aims to help students develop good study habits of their own, in order to enable the students to succeed across many disparate areas of their studies. In coaching we may well go over material which the student has covered in school, but it will be for the purpose of practising new study techniques or demonstrating the effectiveness of different habits rather than to consolidate the material itself.

Sometimes coaching approaches problems that are a little deeper. A student may begin doing badly in a particular subject, and parents sometimes think this indicates that the child needs a tutor for that subject. However the coaching approach would look at the underlying psychological reasons why the student’s performance in that subject deteriorated. It may be, for example, that there are problems of self-esteem or anxiety underpinning the student’s problems. Do read our case studies for examples of how this occurs in practice.

What is academic coaching?

Our academic coaching approach uses a range of techniques taken from disparate fields such as Cognitive Behavioural Therapy and management consulting, and combines these with some of the most up-to-date research on study skills and mental well-being, with the ultimate aim of unleashing your child’s academic potential.

Typical issues which can be addressed through academic coaching are:

- Bad time management;

- Lack of organisation;

- Poor study skills;

- Lack of motivation;

- Failure to plan ahead;

- Problems of social interaction;

- Excessive anxiety;

- Low self-esteem.

Typical symptoms of a problem might be:

- School anxiety and school avoidance;

- Working late into the night;

- Never feeling ‘on top of things’;

- Doing worse in tests than in homework;

- Rushing or spending too long on homework;

- Forgetfulness;

- A sudden decline in grades;

- Poor results despite hard work.

Jake: Anxiety

THE PROBLEM

A year ago, 12 year-old Jake would come home from School brimming with what he had learnt. After a snack and a few cartoons, he would get down to do his homework on the kitchen table, often asking his mum what she thought and showing her what he’d done when he was particularly proud. The past year has changed Jake somehow. He is now silent in the car on his way home, and stares out of the window whilst listening to music with his earphones on. Once home, Jake heads up to his room, shutting the door and coming back downstairs only to grab something to eat. He no longer talks to his mum about what he learns at school. He no longer shows her his homework. His teachers say that he is withdrawn and silent in lessons, unlike the little boy who had his hand up to every question the teacher posed a year earlier. His homework is now often late and incomplete, but his mum is at the end of her tether.

THE CAUSES

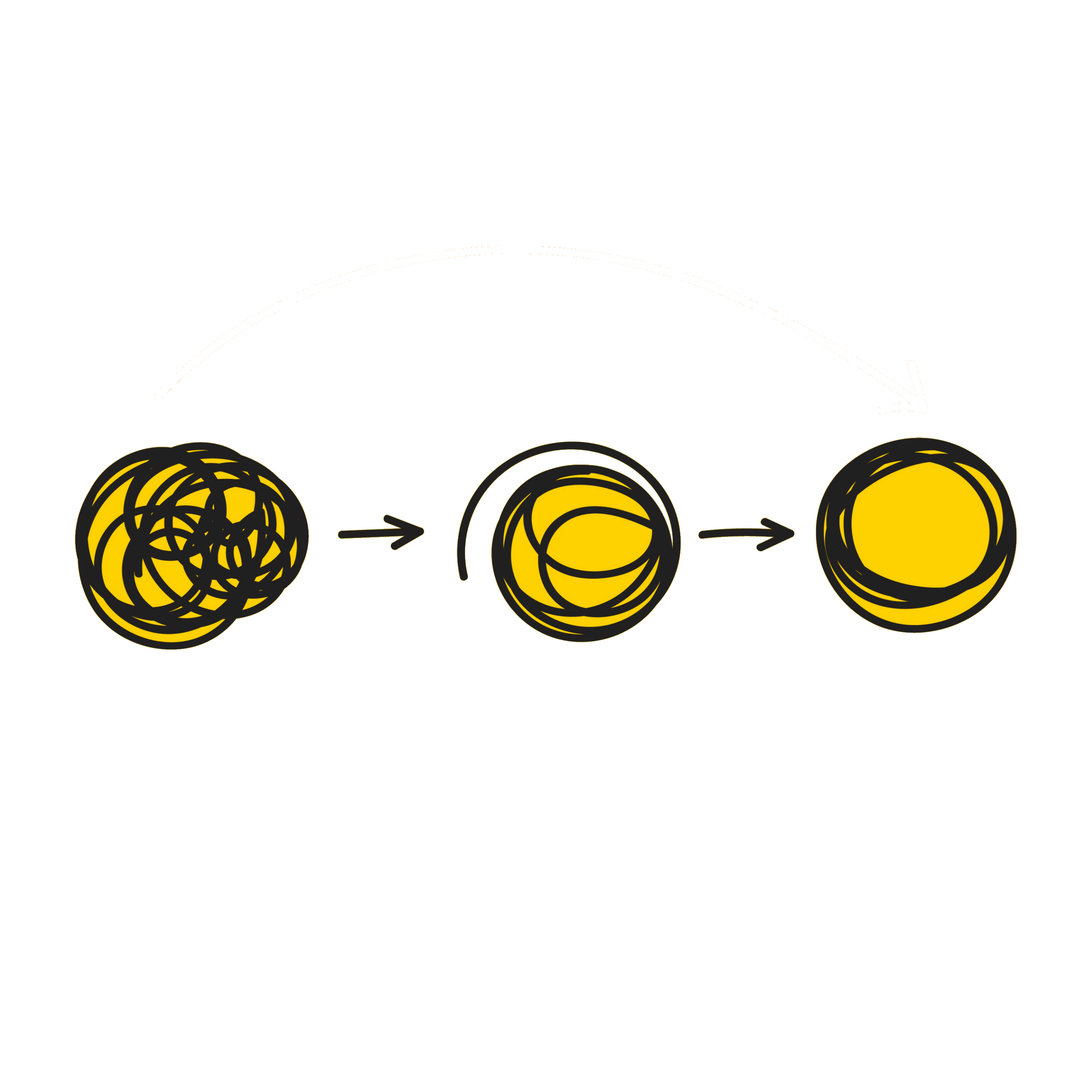

The root of his problem was identified as having been the onset of puberty. This in turn meant that he started losing the thread of what he was studying, and once lost that impacted his grades in homework and tests. He tried harder to focus in lessons and spent longer on his homework, but his efforts were fruitless and he started thinking that perhaps he had reached the limits of his ability, and that no matter how much effort he invested it was not going to improve matters. He started seeking solace in other activities: his friends, video games, TV. This led to Jake spending less and less time on his work, and his grades suffered further.

THE SOLUTION

Jake had four sessions of coaching. During these he was encouraged to recognise the vicious circle that he was in, and to understand how his thoughts and behaviours were contributing to it. Together we identified self-helping thoughts and actions which Jake could use to reassure himself whenever he felt inadequate and through practising these Jake managed to return on track.

Charlotte: Friendship Issues

THE PROBLEM

Charlotte had started Year 7 well, having come from a small primary school to a much larger secondary school. Her parents had hoped that as several of Charlotte’s class mates had also transferred from her same primary she would integrate well. However after the first term Charlotte became increasingly agitated at the thought of going to school. She would throw up regularly before school and spent several Sunday evenings crying in her room at the thought of going to class the next day. Charlotte’s mother sent her to see us after Charlotte had tried to throw herself out of the moving car on the way to school one morning.

THE CAUSES

Charlotte had found that while at primary school she had been friends with everyone in her year, she was increasingly socially isolated at secondary school. The cause of this was identified as her way of maintaining friendships: Charlotte made a point of spending a little time every day with each person in her year. In a small primary school this had worked well and Charlotte had been one of the most popular girls in her class. In the much larger secondary however Charlotte was spreading herself too thin. She was spending barely a few minutes with each person in her effort to get around everybody. This meant that nobody considered her a ‘friend’ but rather saw her as a ‘hanger on’ of the newly-forming friendship groups.

THE SOLUTION

Charlotte had three coaching sessions. In the first session we identified the causes of the problem and Charlotte realised that her friendship strategy was not working. In the second session we identified possible solutions and changes of strategies. We practised these through role play, and Charlotte’s homework that week was to begin using them at school. The strategies were finessed in the third session, and Charlotte very quickly after that returned to her cheery self. She rapidly found her place in a smaller but close-knit group of friends.

How it works

Coaching is done in weekly sessions that are usually about one hour long.

In the first session we will identify what the main barriers to effective academic progress are, and decide which problems we will tackle. Depending on the range of problems to be tackled there may be time to address some of them in the first session.

The sessions can vary in format, depending on what types of problems we need to address. For example, it may be appropriate to use a session to learn new study skills, and this would involve explanation and practice of these techniques. In other cases it may be more useful to explore emotional and cognitive issues using CBT techniques. In these cases typically the pupil will talk about their experience of problematic situations and the coach will help them to understand how they may react to these in constructive ways in future.

Between sessions your coach will set you ‘homework’. These are not your typical homework tasks though! They may involve gathering information by asking people questions or keeping a thought diary in certain situations, or ‘taking the plunge’ and doing something you wouldn’t normally do. These homework tasks are very important as they often give the pupil a chance to try out strategies discussed in the session and they almost always inform the following session.

Academic coaching is a brief intervention: the majority of issues can be addressed in three sessions or fewer; almost all cases can be resolved in six sessions or fewer.

Ethics and confidentiality

Working with children we must be mindful to safeguard all parties, but pay particular attention to the ongoing well-being of the child. To this end, if a problem emerges which requires the intervention of a different professional figure such as a Counselling Psychologist or a Psychiatrist we will always inform you and, should you wish, we may at times be able to advise you about how to find a suitable professional.

Confidentiality is a worry for some parents: on the one hand we recognise that a parent wishes to be informed of their child’s thoughts or emotional state. This needs to be balanced, however, by the need for the child to feel comfortable talking to the coach. Often the child will not ‘open up’ if they believe that everything they say will be recounted to their parents. To achieve this balance we will ask you to sign an agreement that the conversations between coach and child will remain confidential; on the other hand, if an issue arises which you need to know about in the interest of the child, we will disclose it. Furthermore we will always encourage the child to disclose the content of our conversations to you.

We have never encountered a situation where either the parent or the child was displeased by our disclosure (or lack of it) of the content of the sessions.

There may, on very rare occasions, be legal guidance regarding disclosure of information. Please ask us if you wish to know more.

Pricing

The current COVID-19 pandemic and the ensuing lockdown have hit the finances of many families hard. As a consequence we have changed our practice and will – for a limited time – run sessions via video link and we have dropped our prices by 50%. Video sessions can be run on the Zoom platform or via WhatsApp.

Temporary COVID-19 Discounted Rates

The first session is now offered at the discounted rate of £30.

Further sessions are now charged at £60 per session.